Templates

Web frameworks often need to generate dynamic content to render on web pages. And because Django is a web framework, it provides a convenient way to generate HTML dynamically.

Dynamic content

Dynamic content is any data that changes according to context, user behavior, and preferences.

Developers can use dynamic content and rendering to produce static HTML code. The most common approach for developers is to use templates.

Template

Templates are text-based documents or Python strings marked up using the Django template language, or DTL for short. Templates consist mainly of two types of content. The first is static. This is the HTML that does not change on the web page. The second is template language. This is the syntax that allows you to insert dynamic data.

<h2> My first name is {{ dish_name }} and my favorite dish is {{ price }}. </h2>In this example, the variables dish_name and price are placed within the double curly braces. These variables represent dynamic content.

The remaining content, including the HTML heading tags, is static. It’s important to understand that the static part defines the structure and layout of the page and a view using the render function handles the processing of the dynamic content.

def about(request):

info = {'first_name': 'John', 'dish': 'Pasta'}

return render(request, 'specials.html', {info: 'info'})Render

You may recall that the render function takes three parameters: request, path, and a dictionary of variables.

Rendering

When you pass the dictionary object to the render function, the process of rendering replaces variables present with their values which are looked up in the context.

While you use template language to render dynamic content, the concept of a template is what makes up the presentation layer of the MVT architecture. This helps in the separation of logic because templates handle the user interface logic of a web page.

It’s important to know that the dynamic content inside the static HTML is written so Django can understand the syntax and formatting.

DTL

Python is a dynamic object-oriented programming language, while HTML is a static markup language. To bridge this gap, Django makes use of the Django template engine. And the Django template language, or DTL, is the language used for adding dynamic content.

DTL can contain embedded dynamic content, such as Python code and variables that the template engine processes. DTL consists of constructs such as variables, tags, filters, and comments. Each construct has a specific syntax that helps Django understand the code logic.

For example, you can use tags and comments to build a for loop to display list item elements. The tags map the dictionary values from the context and helps to add logic to the template.

<ul>

{% for item in menu %}

{% This is how you comment inside a template %}

<li> {{ items.menu_item_name }} </li>

{% endfor %}

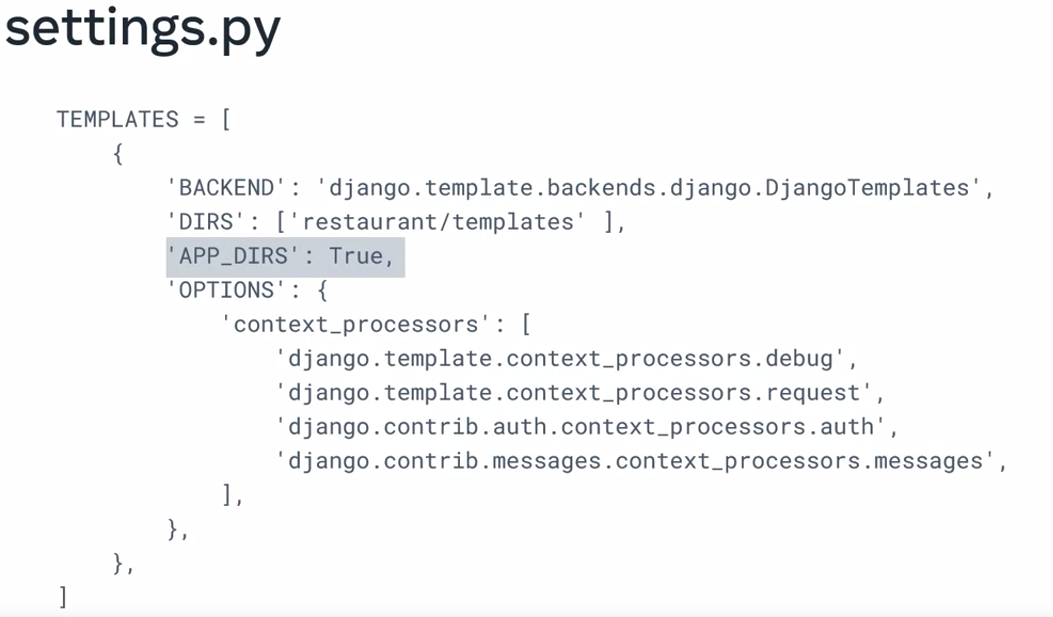

</ul>Additionally, Django also provides an API for loading and rendering templates. You define the configuration settings for the template engine inside settings.py under the project directory.

It’s important to note that the app directory setting must be set to true.

This setting tells Django where to search for templates. For example, search inside a subdirectory named templates for each application in the project. You can also add specific locations inside the directory setting for Django to search for directories inside the DIRS option.

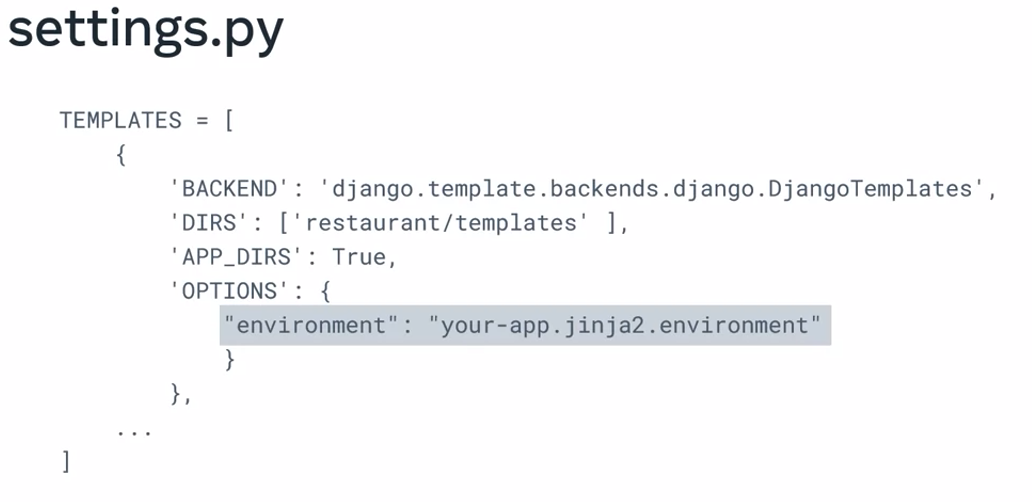

In addition to the Django template engine provided by Django, you can also extend the functionality by using one or more template engines. For example, Jinja2 is a popular template engine used in Python and you can configure the settings for adding these extensions inside the settings.py file. For example, you can change the default environment settings for Django to use Jinja2.

Code Reuse

Django helps in code reuse by using templates with the help of something called template inheritance.

Template inheritance allows developers to build a base template containing the expected HTML elements of your site and defines blocks that child templates can override. Once defined, all pages of the website can inherit the base template.

This code reusability helps in saving developers time and effort and follows the principle of dry.

For example, you can create a base template containing the HTML code for your site’s head, body, and main sections. Then, in a child web page, you inherit the base template and place the specific content of the page.

TIP

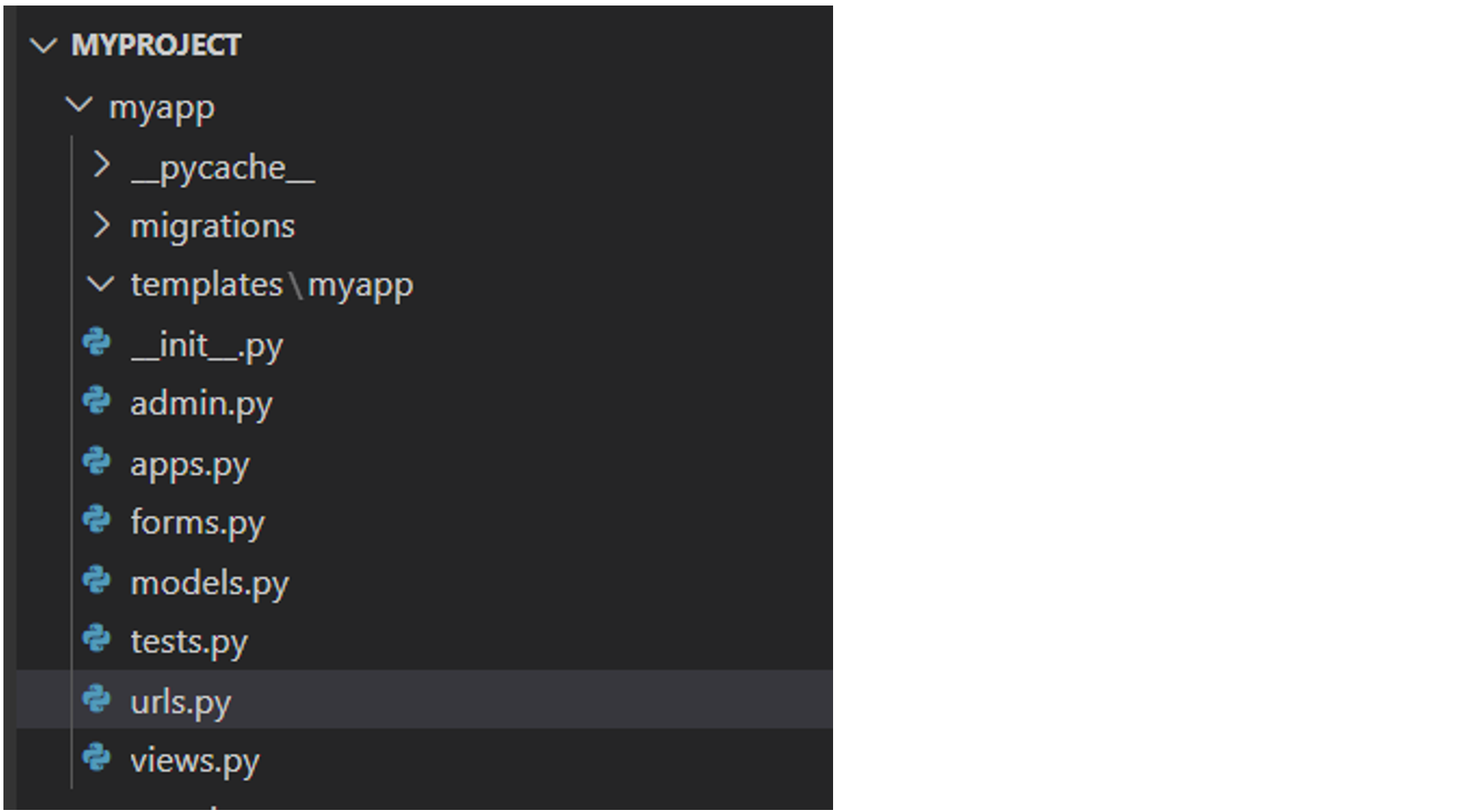

It’s a standard best practice to place template files inside a template folder.

Template Examples

In this reading, you will be introduced to simple template code examples covering variables and filters. More in-depth explanations and examples are provided in a later lesson.

HTML response

Django’s view function returns a HttpResponse whose content-type header is ” text/html” by default. So, if it enters a string, it is rendered as HTML on the browser. The string itself may have certain HTML tags embedded in it. Accordingly, the browser interprets the tags and renders them.

Look at the following view function. It returns a string with Hello World tucked between <h1> and </h1> tags.

from django.http import HttpResponse

def index(request):

return HttpResponse("<h1>Hello, world. </h1>") Let’s say that the app is properly configured and that it is included in the INSTALLED_APPS, and the function is mapped to the appname/ URL in the urls.py file, you’ll get the Hello World message in the H1 tag.

You can write the entire web page script in a string and use it as an argument to the HttpResponse. But what if there is some variable information in between the static HTML?

For example, let’s reference the code block above.

What happens if you want to say Hello to a person whose name appears in the URL as a parameter? You can use Python’s string substitution and pass it as a response.

from django.http import HttpResponse

def index(request, name):

return HttpResponse("<h1>Hello, {}. </h1>".format(name)) Generating HTML from Python code takes time and can be complicated. It needs frequent escaping, especially if there are many variables.

Introducing certain conditional logic will be more difficult. That’s when you use the templates.

A template is an HTML file with placeholders for variable data marked by a special syntax. Django uses its own template language called Django Template Language (DTL). Just the HTML, the DTL has its own tags that control how the variable part is filled.

To replace the Hello World, create a hello.html file and place it in the templates folder in the Django project’s BASE_DIR.

<html>

<head>

<title>My django website</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Hello World</h1>

</body>

</html> Rendering a Template

In the view function, import the loader class from the django.template module and obtain the template object from hello.html. You can now render it as the HttpResponse.

from django.http import HttpResponse

from django.template import loader

def index(request):

template = loader.get_template('hello.html')

context={}

return HttpResponse(template.render(context, request)) If it seems slightly complicated, Django provides a shortcut method called render(). It eliminates the HttpResponse and loader classes.

from django.shortcuts import render

return render(request, 'hello.html', {}) Variable tag

In the above code, the render() function’s third parameter is an empty dictionary object. It is called the template context. You should pass the path parameter as a context to hello.html.

from django.shortcuts import render

def index(request, name):

context={"name":name}

return render(request, 'hello.html', context) Modify the hello.html file by replacing World with the Django variable syntax. Put the key of the context dictionary name inside double curly brackets as in {{ name }}.

<html>

<body>

<h1>Hello {{ name }}</h1>

</body>

</html> You can use {% if %} tag of DTL to implement a conditional logic inside the template. Similarly, with {% for%} and {% endfor %} tags, a looping construct can be built in the template, which may be useful to display records from a database table on the web page. Django’s Template Language has many more tags. You’ll explore this in a subsequent lesson.

Filters

Another important part of Django Template Language is the filters. While tags may be considered similar to keywords in a programming language, the filters merely represent the temporarily modified value of a template variable. The filter is applied to a variable by the**|**(known as Pipe) symbol, such as:

{{ variable_name | filter_name }}Here are some filters in action. The index() view in the above examples receives a name parameter, and it is rendered in the template with the {{ name }} expression tag. If you apply the upper filter to it, the name will be rendered in uppercase.

{{ name | upper }}As a result, if the path parameter passed to the view is John, it will be rendered as JOHN.

Likewise, the lower filter converts the string to its lowercase, the title filter renders a string so that the first letter of each word in a multi-word string appears in uppercase. Therefore, the string “simple is better than complex” becomes “Simple Is Better Than Complex”.

The length filter works with a list and returns the number of items in it. The view passes a list as a context to the template: nums=[1,2,3,4]

The template filter {{ nums | length }} outputs 4

The wordcount filter is similar. It tells you how many words are present in the template variable that has to be a string. For example:

String = 'Simple is better than complex'

is passed a context,

{{ string | wordcount }} returns 5.

The slice filter resembles Python’s slice operator, which separates a part of the given list object. So, if:

nums = [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

Is passed in the context,

{{ nums | slice[1:3] }}

It returns [2,3] and then you can iterate over it.

The first and last filters return the first and last item in the list.

Like the tags, Django also has a large number of filters. You’ll learn more about these tags in a forthcoming lesson.

Creating Templates

Webpage design can become time-consuming, especially if you work with dynamic webpages. When building a web application in Django, templates provide developers with many benefits. One of the main benefits is that they promote code reusability and render dynamic content.

The view functions retrieve the data from some data structure, our database connected to our application. Developers use templates and the Django template language to display this dynamic data.

Templates contains static HTML and dynamic data rendered by the render function. The render function takes three parameters: request, path, and a dictionary of variables.

def about(request):

return render(request, 'specials.html', {"name": 'Specials'})- Request, represents the initial HTTP request to object.

- Path, represents the relative path of the HTML file to the template directory or folder.

- The dictionary contains the variables as keys that the template can use to display dynamic data.

render function

The render function returns a string as part of the HTTP response object that the web page renders. Since this process is created inherently with Python code, there is flexibility to define and pass variables to the template.

Creating a template

First, you define a view that returns the render function.

def about(request):

return render(request, 'about.html', {"name": 'About us'})Next, update the URL configurations inside URL patterns,

urlpatterns = [

path('about/', views.about, name="about"),

]then ensure that you configure the settings for templates and installed apps.

INSTALLED_APPS = [

# ...

'restaurant',

]Next, create a HTML page containing static HTML and dynamic data using the Django template language.

{% block content %}

<section>

<article>

<h1>{{ Name }}</h1>

<p>Little Lemon is Mediterranean restaurant.</p>

</article>

</section>

{% endblock %}Finally, make sure you pass the name of the template page and dictionary as arguments inside the render function.

def about(request):

return render(request, 'about.html', {"name": 'About us'})

WARNING

Templates folder is created in the project level.

NOTE

Notice that within the about.html file,by typing an exclamation mark and selecting the first option, VS Code will automatically create the code for a basic HTML page.

PythonDjangoTemplateHTMLFront-end

Previous one → 11.Database Configuration | Next one → 13.Working with Templates