What is a module in Python?

What is a python module?

Imagine that modules work like instructions to make a pie. Instead of trying to figure out what the steps are to create your pie, you follow the instructions.

Modules work in the same way. They are building blocks for adding functionality to your code, so you don’t need to continually redo everything.

A Python module contains statements and definitions. A file like sample.py can be a module named sample, and can be imported. Modules in Python can contain both executable statements and functions.

Value and purpose of modules

Modules come from modular programming. This means that the functionality of code is broken down into parts or blocks of code. These parts or blocks have great advantages which are:

- scope

- reusability

- simplicity

Everything in Python is an object, so the names that you use for functions, variables, and so on become important.

Scope

Scoping means that modules create a separate namespace. Two different modules can have functions with the same name, and importing a module makes this a part of the global space in the code being executed.

Reusability

The most important advantage!

When you write a piece of code, modules help you avoid the need to write all the functionalities that you may need. Duplication of code, duplication of efforts uses more computer memory and it’s less efficient.

Simplicity

When modules have a little dependency on each other, it helps achieve simplicity. Each module is built with a simple purpose in mind. Modules are defined by their usage.

You can also use a regular expression or RE module for managing regular expressions.

Simplicity also helps in avoiding interdependency among these modules.

If you’re working on data visualization, import of a single module like Matplotlib is sufficient for visualizing your data.

Differences of module

The main difference between these modules is the way the modules are accessed.

Some modules are already built into the standard Python library.

When you use a statement like Import math in your Python code for example, the interpreter first tries to find a built-in modules.

NOTE

The first important thing to know is that modules are imported only once during execution.

Since modules are built to help you, stand-alone modules hold all the functions, but will most likely not contain functions that execute without calling. It’s only when the user executes the different functions inside that module that they will find the utility of those functions in the code.

NOTE

The module is normally defined at the beginning of the code, but you can define it at any point in the code. Since code execution in Python is serial, you must import the module first before you execute any function inside of it.

Modules can also be executed from within the function. This means that the code inside that module can only be used once the function is executed.

Accessing modules

WARNING

Any python file can be a module.

The modules are searched by the interpreter and the following sequence:

- Current directory path

- built-in module directory

- Python path environment variable with a list of directories

- It investigates the installation dependent default direcotry

Examples

import sys

locations = sys.path

print(locations)The print function returns all the possible locations that the interpreter is going to look for when searching for modules, including the current working directory.

# A Cleaner view

import sys

locations = sys.path

for i in locations:

print(i)import sys

locations = sys.path

for i in locations:

print(i)

import calendar

leapdays = calendar.leapdays(2000, 2050)

print(leapdays)

isitleap = calendar.isleap(2036)

print(isitleap)TIP

ctrl + click on the

calendartakes you to thecalendar.pyfile. Note how the calendar module itself has imported a few other modules, and other than that, it contains all the functionalities.

The import statement

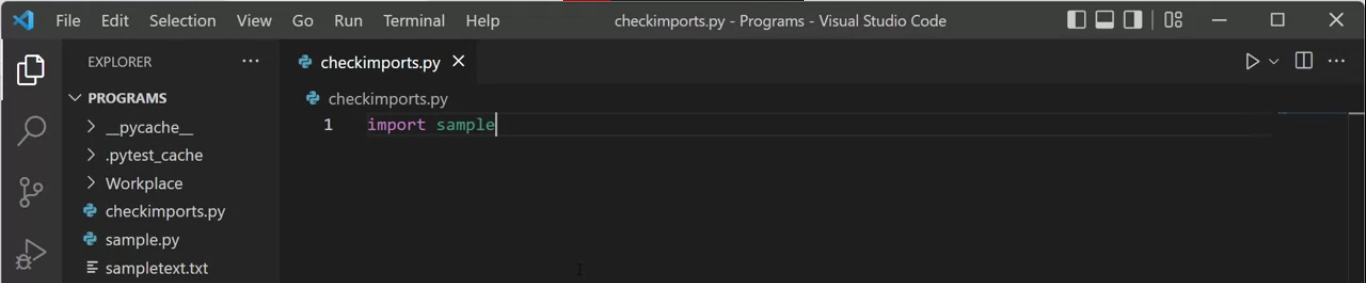

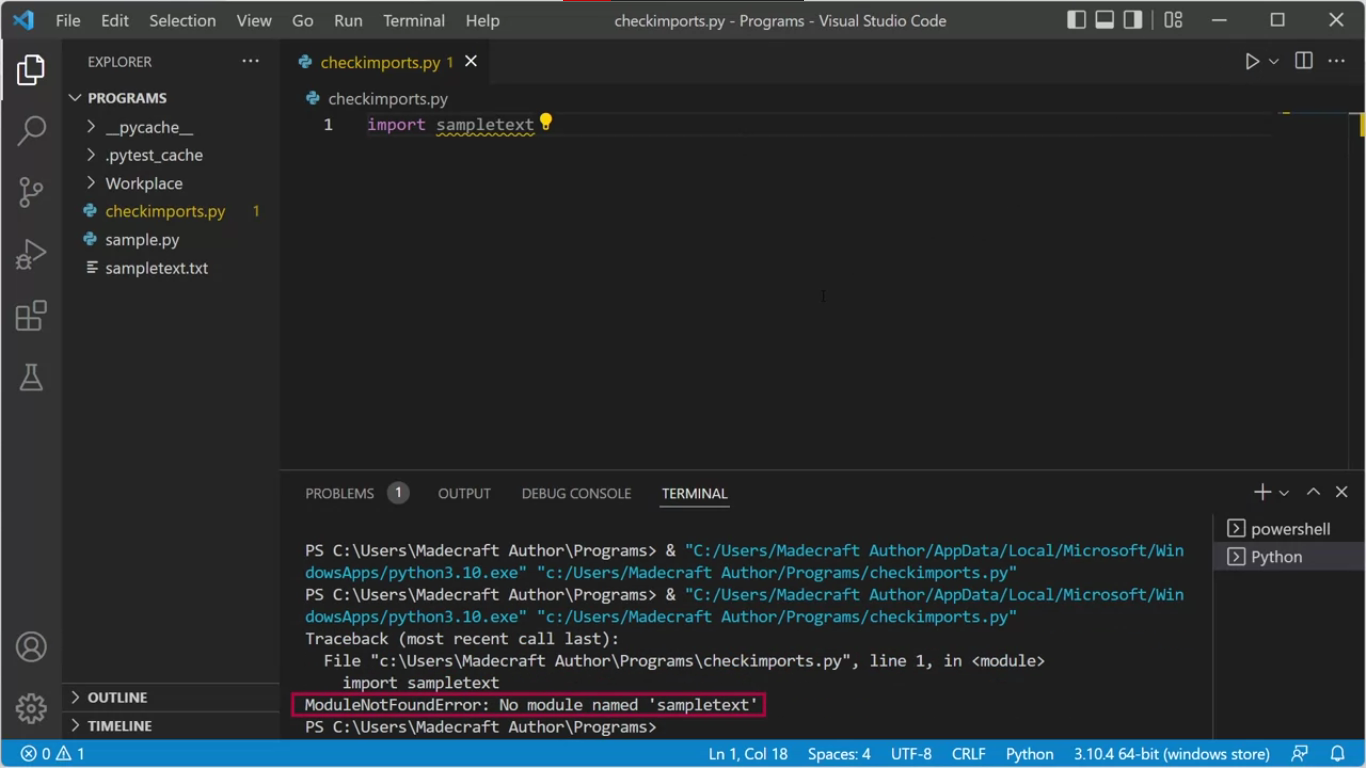

Every python file, which means any file with a .py extension containing a script is effectively a module. The checkimports file I am currently creating, is therefore a module for some of the files.

The code that you are working with is generally called the main module. In this case checkimports is the main module present in the current working directory. Also called the scope of the project.

INFO

Python has a library of standard modules called built in modules. These modules are directly built into the python interpreter and don’t have to be installed separately.

The list of built in modules can be found in the python standard library. You can think of packages as the structuring of python modules as a collection.

NOTE

Special files called

init.pyfiles are required for python to treat directories containing the file as packages.

Python has a rich collection of community built packages that I could find on the python package index, or pyPI.

INFO

piporpip3is the default package installer for python, and helps with the installation of packages from pyPI.

Package installation

pip install <Package Name>

to install packages from pyPI index.

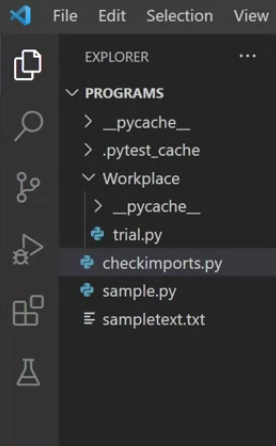

Modules from another directory

import sys

sys.path.insert(1, r'C:\Users\Madecraft Author\Programs\Workplace')

import trial

print(trial.names)Writing import statements

import math

print("Importing tha math module")Importing tha math moduleMost of the modules that you will come across, especially the built-in modules, will not have any print statements, and they will simply be loaded by the interpreter.

import math

root = math.sqrt(9)

print(root)3.0Instead of importing the entire math module as we did above, there is a better way to handle this by directly importing the square root function inside the scope of the project.

This will prevent overloading the interpreter by importing the entire math module.

from math import sqrt

root = sqrt(9)

print(root)Alias

import math as m

cosine = m.cos(0)

print(cosine)1.0Alias for Functions in a module

from math import factorial as f

factorial_10 = f(10)

print(factorial_10)3628800Importing multiple functions

from math import factorial, log10, sqrt

x = log10(50)

print(x)1.6989700043360187Importing all functions inside a module

from math import *

x = log10(50)

print(x)1.6989700043360187Importing packages is very similar to importing modules in Python. Just like you can have imported functions, you could also import variables and classes from a given module.

Namespacing and scoping

INFO

The official Python documentation defines namespace as mapping from names to objects, and scope is the textual region of a Python program where the namespace is directly accessible.

At this point, the dictionary with its key value pairs serves as the ideal data structure for the mapping of names and objects.

You can view the same module as a place where Python creates a module object. A module object contains the names of different attributes defined inside it.

In this way, modules are a type of namespace. Namespaces and scopes can become very confusing very quickly, and so it is important to get as much practice of scopes as possible to ensure a standard of quality.

There are four main types of that can be defined in Python:

- local

- enclosed

- global

- built-in

[[3.Functions and Data Structures#[Function and variable scope](https //www.coursera.org/learn/programming-in-python/supplement/PmZPi/function-and-variable-scope)]]

Scope Resolution

The practice of trying to determine in which scope a certain variable belongs is known as scope resolution.

Scope resolution follows what is known commonly as the LEGB rule.

Local

This is where the first search for a variable is in the local scope.

Enclosed

This is defined inside an enclosing or nested functions.

Global

Global is defined at the uppermost level or simply outside functions.

Built-in

Which is the keywords present in the built-in module.

NOTE

In simpler terms, a variable declared inside a function is local, and the ones outside the scope of any function generally are global.

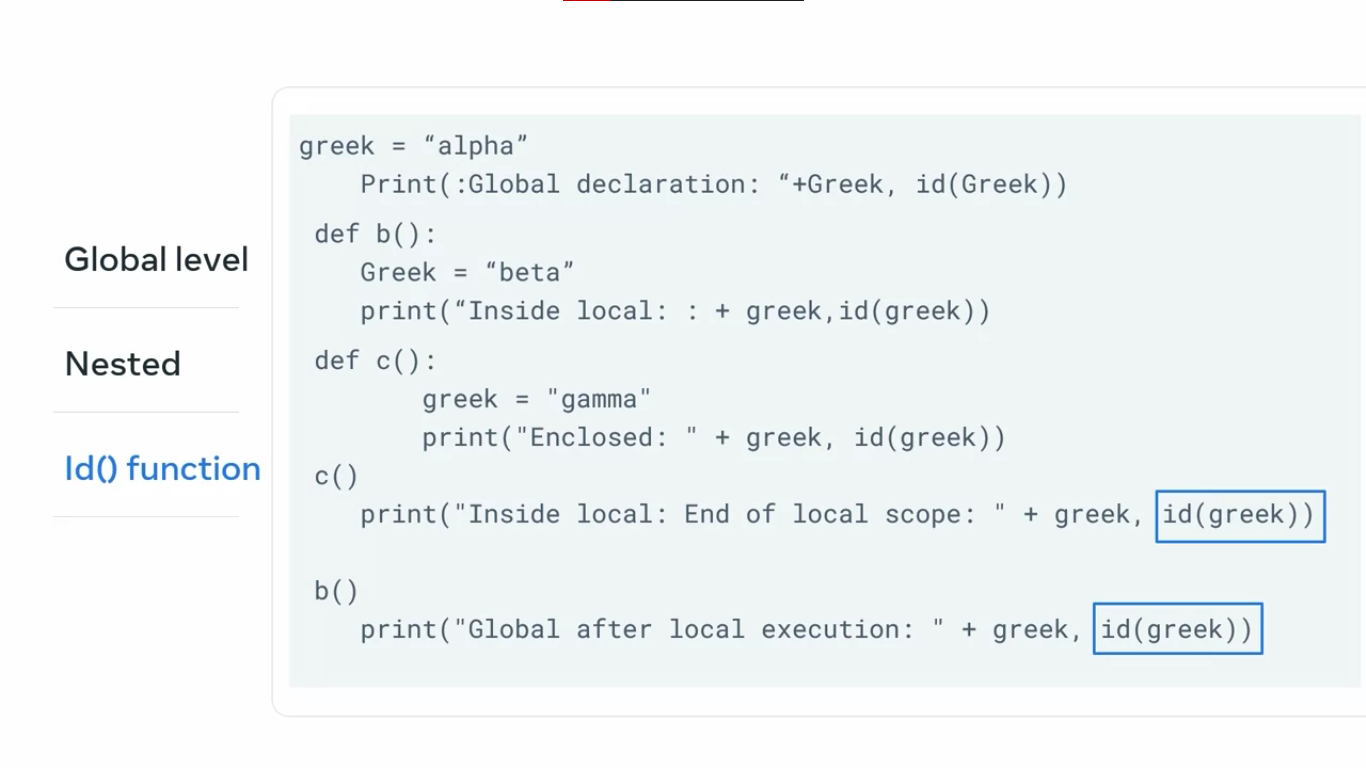

INFO

The id function is used here in the print statements, which returns the identity of the objects.

You can make some observations from the output.

- The id for the global variable alpha remains same as defined after the code is completely executed.

- The id for the local variable beta inside the function b remains unchanged before and after the execution of nested function c.

- The id for Gamma is assigned only within the scope of the nested function.

- The id for all three variables is different even if they all have the same variable name.

Variables in Python are implicitly declared when you define them. That means, unlike other programming languages, there is no special declaration made in Python for the variable which specifies its datatype.

What it also implies is that a given variable is local, not global when it is declared unless stated otherwise.

This contrasts with most other programming languages where variables are global by default.

When a variable is declared in a global space, it is also local to that space.

While global variables are acceptable, they’re discouraged for a number of reasons. When you are working with production code, the project structure can get complex, and working with global variables can be hard to diagnose which lead to what is called the spaghetti code.

Other paradigms such as access modifiers, concurrency, and memory allocation are better handled with local variables.

Global & None-Global

There are two key words that can be used to change the scope of the variables, global and non-local.

The global keyword helps us access the global variables from within the function.

Nonlocal is a special type of scope defined in Python that is used within the nested functions only in the condition that it has been defined earlier in the enclosed functions.

def d():

animal = "elephant"

def e():

nonlocal animal

animal = "giraffe"

print("Inside nested functions: " + animal)

print("Before calling fucntion: " + animal)

e()

print("After nested function: " + animal)

animal = "camel"

d()

print("Global animal: " + animal)Before calling fucntion: elephant

Inside nested functions: giraffe

After nested function: giraffe

Global animal: cameldef d():

# animal = "elephant"

def e():

nonlocal animal

animal = "giraffe"

print("Inside nested functions: " + animal)

print("Before calling fucntion: " + animal)

e()

print("After nested function: " + animal)

animal = "camel"

d()

print("Global animal: " + animal)Traceback (most recent call last):

File "PATH", line 198, in _run_module_as_main

return _run_code(code, main_globals, None,

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

File "c:\Users\usr\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python312\Lib\runpy.py", line 88, in _run_code

exec(code, run_globals)

File "c:\Users\usr\.vscode\extensions\ms-python.debugpy-2024.4.0-win32-x64\bundled\libs\debugpy\adapter/../..\debugpy\launcher/../..\debugpy\__main__.py", line 39, in <module>

cli.main()

File "c:\Users\usr\.vscode\extensions\ms-python.debugpy-2024.4.0-win32-x64\bundled\libs\debugpy\adapter/../..\debugpy\launcher/../..\debugpy/..\debugpy\server\cli.py", line 430, in main

run()

File "c:\Users\usr\.vscode\extensions\ms-python.debugpy-2024.4.0-win32-x64\bundled\libs\debugpy\adapter/../..\debugpy\launcher/../..\debugpy/..\debugpy\server\cli.py", line 284, in run_file

runpy.run_path(target, run_name="__main__")

File "c:\Users\usr\.vscode\extensions\ms-python.debugpy-2024.4.0-win32-x64\bundled\libs\debugpy\_vendored\pydevd\_pydevd_bundle\pydevd_runpy.py", line 320, in run_path

code, fname = _get_code_from_file(run_name, path_name)

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

File "c:\Users\usr\.vscode\extensions\ms-python.debugpy-2024.4.0-win32-x64\bundled\libs\debugpy\_vendored\pydevd\_pydevd_bundle\pydevd_runpy.py", line 294, in _get_code_from_file

code = compile(f.read(), fname, 'exec')

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

File "c:\Users\usr\Desktop\Test\test.py", line 4

nonlocal animal

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

SyntaxError: no binding for nonlocal 'animal' foundreload() function

The reload function reloads an imported module in Python. The only precondition is that the argument passed to it must be a module that has already been successfully imported within the program.

The import is done just once, even if you write import module multiple times.

# sample.py

print("Hello word")# reloads.py

import sample

import sample

import sampleHello word# reloads.py

import importlib

import sample

importlib.reload(sample)

importlib.reload(sample)

importlib.reload(sample)Hello world

Hello world

Hello world

Hello world

# reloads.py

import importlib

import filechanges

def changes():

try:

importlib.reload(filechanges)

filechanges.print_changes()

except:

pass

for i in range(5):

changes()

input('Hit enter to reload...')# filechanges.py

import os

def print_changes():

contents = os.listdir(r'C:\Users\Madecraft Author\Programs')

print("Current directory contents:")

print(contents)Now if you add or delete files in your directory, you will see the changes.

Module Use-cases

So far you have learned about modules, packages and libraries in the context of using modules in Python. The third-party packages in Python are in most cases open-source, free and available for a wide variety of domains. These resources extend the functionality of Python programs beyond the built-in modules and are one of the main reasons why Python is popular today.

Before you learn how to install and use these packages, let’s briefly go through the difference between a module, a package and a library.

Modules, libraries and packages

Modules and packages can easily be confused because of their similarities, but there are a few differences. Modules are similar to files, while packages are like directories that contain different files. Modules are generally written in a single file, but that’s more of a practice than a definition.

Packages are essentially a type of module. Any module that contains the path definition is a package. Packages, when viewed as a directory, can contain sub-packages and other modules. Modules, on the other hand, can contain classes, functions and data members just like any other Python file.

Library is a term that’s used interchangeably with imported packages. But in general practice, it refers to a collection of packages.

Despite the differences between modules, packages and libraries, you can import any of them using import statements.

Third-party package add-ons of Python can be found in the Python Package Index. To install packages that aren’t a part of the standard library programmers use ‘pip’ (package installer for Python). It is installed with Python by default. To use pip, you need to be familiar with either the terminal if you’re using a Mac or the command line interface if you’re using Windows.

Alternatively, you can also use the terminal window present inside your IDE. When you are using the command line or terminal, you must make sure that you are installing packages in the same Python interpreter that you are working with inside your IDE.

While pip usually comes installed with Python by default it might be necessary to check the status of pip installation. If you’re using a Mac, run the following command in the terminal:

python -m ensurepip --upgrade

If you’re using Windows, you run the following command:

py -m ensurepip --upgrade

Once you verify its installation, you can install packages using pip on your machine.

The standard format for using pip command on MacOS is:

python3 -m pip install "SomeProject"

py -m pip install "SomeProject"

Let’s examine an example. If you want to install a third-party package such as ‘requests’, you run the following command on a Mac:

python3 -m pip install requests

For Windows you’d run this one:

py -m pip install requests

Note: Package names as well as the command line or terminal are case-sensitive.

Once you have installed the package, you will be able to use the package directly inside your Python code. This is a one-time installation and the package will be present as a part of your Python interpreter until you choose to uninstall it.

The packages that you can install often have a number of classes, functions, sub-packages and members. These can be understood by using the package and finding examples that other programmers have posted on different websites. This will give you a better understanding of what functionality within that package needs more attention than others.

Additionally, it is also a good practice to look up the documentation of the packages. In some cases, you can use the Python Package Index pypi website. In other cases, the packages are built and maintained by open-source communities and you can find their information on a standalone website created for it or on a version control system such as GitHub. Documentation in most of the popular Python libraries today is pretty elaborate and should have good examples to get you started.

Sub-packages

If we are to assume that packages are similar to a folder or directory in our operating system, then the package can also contain other directories. Packages, both built-in and user-defined, can contain other folders within them that need to be accessed. These are named sub-packages. You use dot-notation to access sub-packages within a package you have imported. For example, in a package such as matplotlib, the contents that are used most commonly are present inside the subpackage pyplot. Pyplot eventually may consist of various functions and attributes.

The code for importing a sub-package is:

import matplotlib.pyplot

To make it even more convenient, it is often imported using an alias. So more commonly, you will come across code such as:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

You could use any other word as an alias instead of plt, but it is a common convention.

You can explore the directory structure of such packages usually by searching for the module index of that package.

Additional resources

Learn more Here is a list of resources that may be helpful as you continue your learning journey.

How To Import Modules in Python 3 (Digital Ocean)

Python Modules (Programiz)

Python Packages (Real Python)

ModuleImportNamespacescopePython

Previous one → 7.Object Oriented Programming | Next one → 9.Popular Packages, Libraries and Frameworks