What is functional programming?

It’s particularly adept at processing large amounts of data at high speeds.

Role of a function

Functions take some input, process it and then produce some outputs.

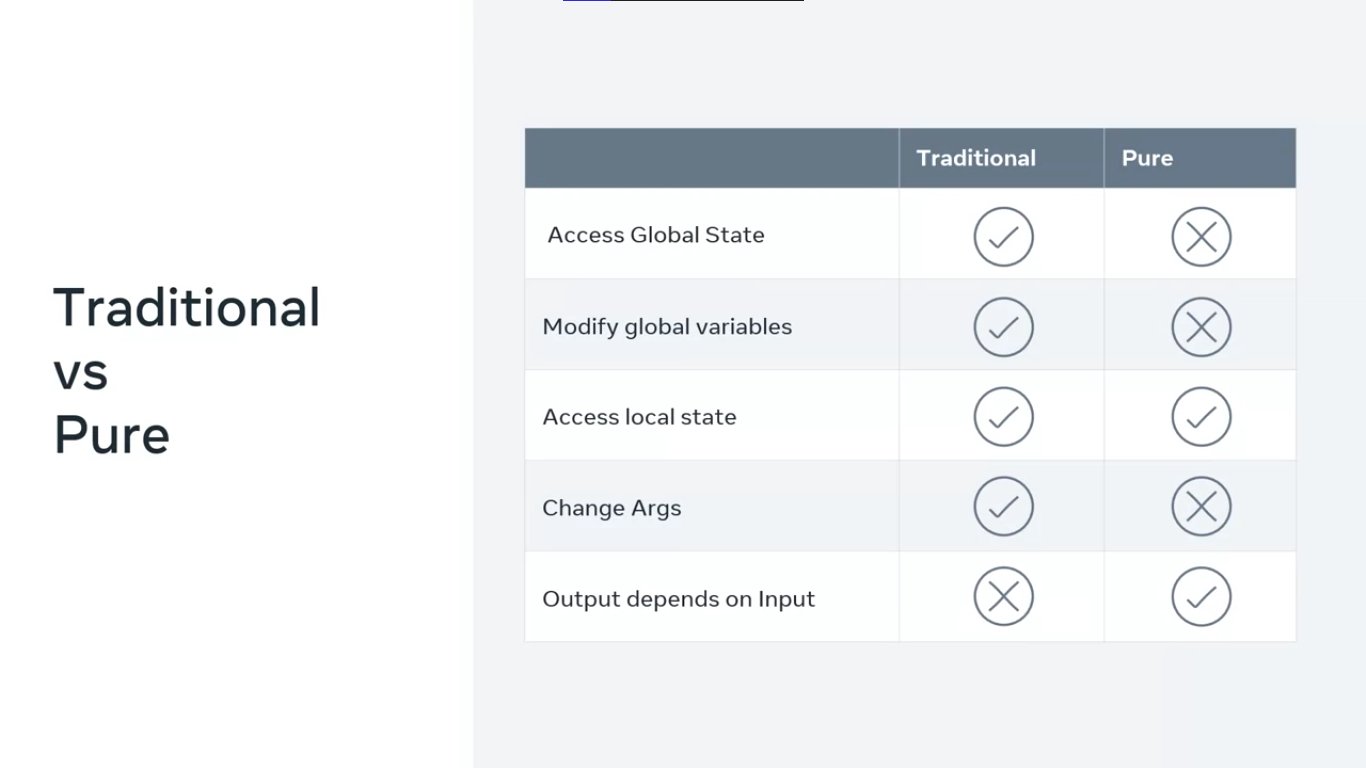

There are two types of functions:

- traditional

- pure

Pure functions will always do the same thing and return the same results no matter how many times they are called.

Functional programming in essence is a programming paradigm that utilizes functions for clean, consistent and maintainable code. Compared to object orientated programming, which we’ll learn about later, functional programming differs by design.

Functional programming does not change the data outside the scope of the function. This simply means that the function should avoid modifying the input data or arguments being passed, instead it should only return the completed result of the intended function being called.

Functions are considered standalone or independent and this aids the clean and elegant nature of the code.

In fact, many of the strongly typed object orientated languages have incorporated function programming into their structure.

In order to support functional programming, the language itself needs to allow function to be passed as an argument and also return a function to its caller.

In python functions are what is known as first class citizens, which essentially means they have the same level of strings and numbers.

They can be

- assigned to a variable

- passed as an argument

- returned to its caller

sorted()

The sorted function accepts a list of items and then returns that list in a sorted order. You can use sorted function to list items in alphabetical order.

The great thing about functional programming is that the logic behind certain tasks is already built in for you.

Functions are reusable and thus save a lot of development time.

Pure functions

It’s important to understand that there is a clear difference between traditional and pure functions. A pure function is a function that does not change or have any effect on a variable, data, list, or sets beyond its own scope.

#global scope

global_list = [1, 2, 3]

def add_to(item):

return global_list.append(item)

add_to(4)

print(global_list)[1, 2, 3, 4]No, it’s not a pure function as it changes the global_list by appending the item which is passed as an argument. In order to change it to a pure function, you need to think how to extend the function to:

- accept a list as an argument

- add the item to the list

- without modifying the original list with the newly added item

def add_to_list(lst, item):

n1 = lst.copy()

n1.append(item)

return n1Benefits of pure functions

- You always know what the outcome will be.

- Pure functions are consistent snippets of code that do exactly what they are intended to do.

- Pure functions include the ability to cash since you know the return is always going to be the same.

- Pure functions blend themselves well to a multi-threaded program.

Multi-threaded programs

In multi-threaded programs, more than one process can run concurrently, which creates many threads of data.

Pure functions will help prevent changes on the global scope ensuring data stays reliable.

Recursion

In programming, recursion is used for solving problems that can be broken down into smaller, repetitive problems.

It’s especially good for working on things that have many possible branches and too complex for an iterative approach.

One good example of this would be searching through a file system.

Recursion

Recursion is essentially a function that calls itself. Recursion creates a pattern of repeating itself over and over and over.

The key part is the return. In the code, the return statement is returning the same function. Recursion is quite similar to a for loop. It will iterate, or in the case of a recursive function, call itself multiple times.

WARNING

When you create a recursive function, you must always consider the results. If you don’t, it will spin into an infinite loop and suck up all the memory until the program eventually crashes or gets terminated.

Advantages

- Recursive code can make your code neater and less bulky.

- Complex tasks can be broken down into easier to read sub-problems.

- Generation of sequences can be easier to understand than nested loops.

Disadvantages

- It can be harder to follow the logic in recursive code.

- In terms of memory, they are expensive and sometimes inefficient.

- It can also be difficult to debug and step through the code.

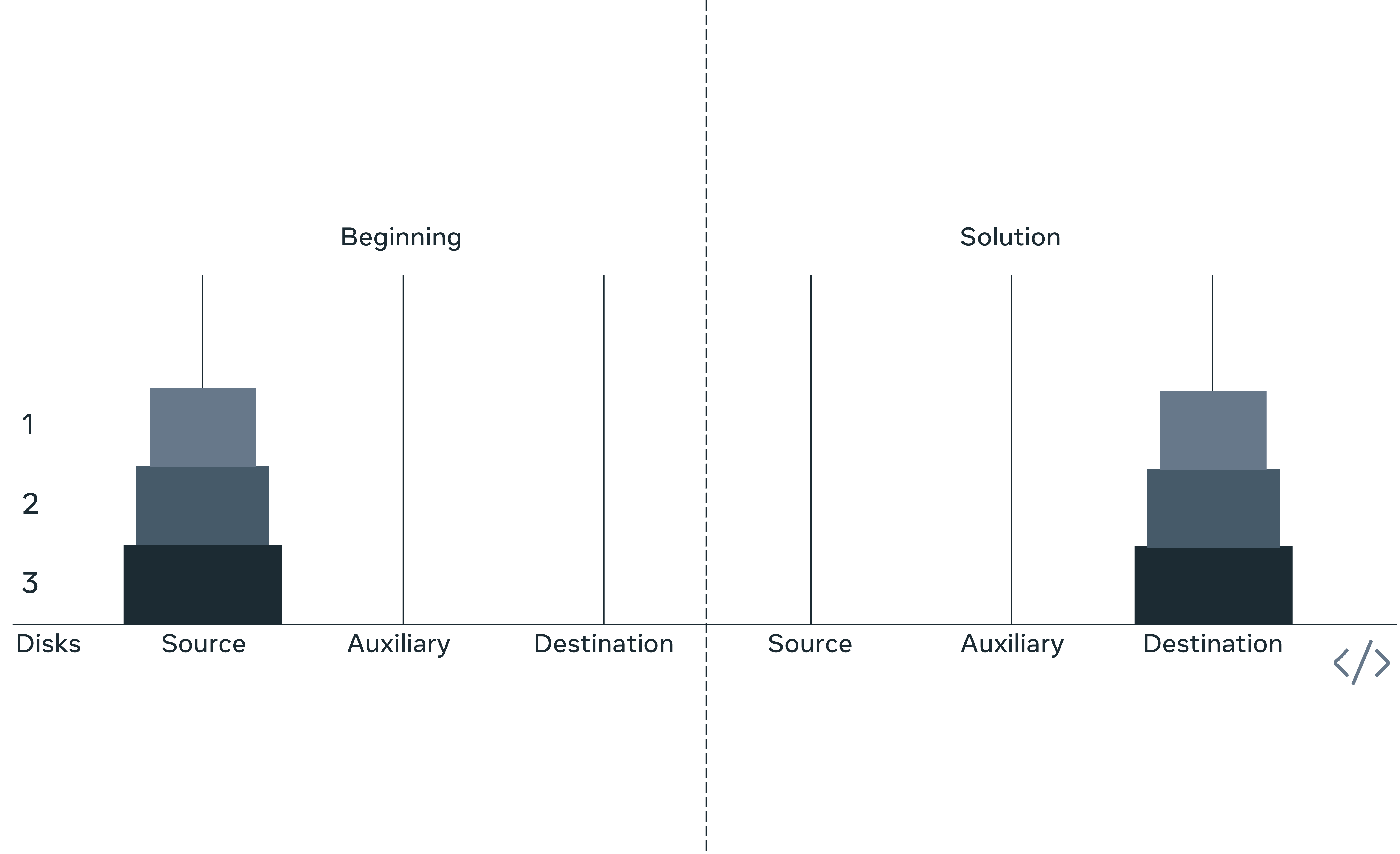

Recursion example: Tower of Hanoi

Introduction

The Tower of Hanoi is a popular puzzle in mathematics and programming. It’s widely considered as a good way to demonstrate recursion. There is a legend about an ancient Hindu temple containing a large room with three posts surrounded by 64 golden disks. The puzzle was presented to a young priest who was told to move all the disks from one post to another without violating a set of given rules. By estimates, if the priest followed the rules and moved one disk per second, the puzzle would be solved in 2^64 – 1 second. That’s about 585 billion years. By then the temple would no longer exist. Inspired by this legend, a French mathematician Edouard Lucas invented the Tower of Hanoi puzzle more than a hundred years ago.

Objective and rules of the puzzle

The objective is to move n number of disks from one tower to another following a set of rules. These rules are as follows:

- Only one disk can be moved at a time

- Only the upper disk of any of the towers can be moved

- Larger disks cannot be placed over smaller disks

An image of the initial and final stages of the puzzle is provided above.

In the optimal scenario of solving the puzzle, the total moves will be 2^n – 1 where n is the number of disks that need to be moved.

Now let’s examine how you can write code for this in Python using the principles of recursion that you have learned.

Understanding codeblocks

You begin with three towers or poles, source destination and helper. In the first section of code, you will cover the base condition of recursion. Base conditions serve primarily to complete the execution and ensure the recursion does not run into an infinite loop.

The second section of code deals with the actual call to the recursion function within itself.

The third section consists of the driver code for the initial call, consisting of the actual tower names that you pass as arguments to the function, along with the number of disks. Driver code is a generic term used to denote the section of code that gives the actual call to the function or class.

# Recursive function for Tower of Hanoi

def hanoi(disks, source, helper, destination):

# Base Condition

if (disks == 1):

print('Disk {} moves from tower {} to tower {}.'.format(disks, source, destination))

return

# Recursive calls in which function calls itself

hanoi(disks - 1, source, destination, helper)

print('Disk {} moves from tower {} to tower {}.'.format(disks, source, destination))

hanoi(disks - 1, helper, source, destination)

# Driver code

disks = int(input('Number of disks to be displaced: '))

'''

Tower names passed as arguments:

Source: A

Helper: B

Destination: C

'''

# Actual function call

hanoi(disks, 'A', 'B', 'C')Number of disks to be displaced: 3

Disk 1 moves from tower A to tower C.

Disk 2 moves from tower A to tower B.

Disk 1 moves from tower C to tower B.

Disk 3 moves from tower A to tower C.

Disk 1 moves from tower B to tower A.

Disk 2 moves from tower B to tower C.

Disk 1 moves from tower A to tower C.Explanation

If you can imagine the disks in question as displayed in the image, you can understand how the code successfully displaces the three disks from tower A to C, following the expected rules.

Note how the variable disk initially takes the number of disks as the input and later is read or understood as the disk number in question inside the code.

In the block of code, the first section is the base condition that that you apply when using disk 1. Once executed, it returns to the rest of the execution flow out of the if condition.

The remaining disks are moved by passing the values from source to helper with destination as helper. The remaining disk is moved from source to destination. The remaining n-1 disks on the helper are moved from helper to destination with source as the helper.

In the last section, the driver code takes the input for the number of disks I want to move. In accordance, I pass the values of A, B and C as the tower names and give the function call.

You will notice that it took 2^3 - 1 = 7 steps to complete the transfer, which meets my expectations.

The Tower of Hanoi and recursion, in general, can be confusing, even for an avid Python programmer. As such, the best way to understand recursion is by inserting the values and running a dry code using a pen and paper to see how the values change and which function gets called in the code at what point.

Reversing a string on Python

Using slice function

Extended Slice Syntax

str[start:stop:step]

trial = "reversal"

new_trial = trial[::-1]

print(new_trial)lasreverUsing recursion

def string_reverse(str):

if len(str) == 0:

return str

else:

return string_reverse(str[1:]) + str[0]

str = "reversal"

reverse = string_reverse(str)

print(reverse)lasreverMap & filter

menu = ["espresso", "mocha", "latte", "cappuccino", "cortado", "americano"]I want to print all coffees that start with the letter C:

map()

The map function accepts two arguments.

- The first argument is an actual function. In this case, it will be the function that I will use to match values based on a condition.

- The second argument is the articles that will be passed through that function. In this case, the coffees from my menu list.

menu = ["espresso", "mocha", "latte", "cappuccino", "cortado", "americano"]

def find_coffee(coffee):

if coffee[0] == 'c':

return coffee

map_coffee = map(find_coffee, menu)

print(map_coffee)<map object at 0x000001C491113430>menu = ["espresso", "mocha", "latte", "cappuccino", "cortado", "americano"]

def find_coffee(coffee):

if coffee[0] == 'c':

return coffee

map_coffee = map(find_coffee, menu)

for x in map_coffee:

print(x)None

None

None

cappuccino

cortado

Nonefilter()

menu = ["espresso", "mocha", "latte", "cappuccino", "cortado", "americano"]

def find_coffee(coffee):

if coffee[0] == 'c':

return coffee

filter_coffee = filter(find_coffee, menu)

print(filter_coffee)<filter object at 0x000002A8EB1C3400>menu = ["espresso", "mocha", "latte", "cappuccino", "cortado", "americano"]

def find_coffee(coffee):

if coffee[0] == 'c':

return coffee

filter_coffee = filter(find_coffee, menu)

for x in filter_coffee:

print(x)cappuccino

cortadoA map takes all objects in the list and allows you to apply a function to it. A filter also allows you to take in all objects in the list and runs through a function but it creates a new list and only returns values where the evaluated function returns true. That is why there are no none values displayed in the output for the filter function.

TIP

Here, because there is no return for the

elseand there is just one if, using the map, it showsNone. But if you write anelseand return something, it will show it.If you use filter, if you put an

elsestatement and returnFalse, it won’t show it. But if you put some other thing, it will show that.

Comprehensions

Comprehensions in Python are a way to create a new sequence from an already existing sequence.

There are four main types of comprehensions in Python:

- List comprehension

- Dictionary comprehension

- Set comprehension

- Generator comprehension

You will now explore each of these to learn how to use them.

List comprehension

The syntax for list comprehension is:

[ <expression> for x in <sequence> if <condition>]

The same can be illustrated with the example below.

data = [2,3,5,7,11,13,17,19,23,29,31]

# Ex1: List comprehension: updating the same list

data = [x+3 for x in data]

print("Updating the list: ", data)

# Ex2: List comprehension: creating a different list with updated values

new_data = [x*2 for x in data]

print("Creating new list: ", new_data)

# Ex3: With an if-condition: Multiples of four:

fourx = [x for x in new_data if x%4 == 0 ]

print("Divisible by four", fourx)

# Ex4: Alternatively, we can update the list with the if condition as well

fourxsub = [x-1 for x in new_data if x%4 == 0 ]

print("Divisible by four minus one: ", fourxsub)

# Ex5: Using range function:

nines = [x for x in range(100) if x%9 == 0]

print("Nines: ", nines)Updating the list: [5, 6, 8, 10, 14, 16, 20, 22, 26, 32, 34]

Creating new list: [10, 12, 16, 20, 28, 32, 40, 44, 52, 64, 68]

Divisible by four [12, 16, 20, 28, 32, 40, 44, 52, 64, 68]

Divisible by four minus one: [11, 15, 19, 27, 31, 39, 43, 51, 63, 67]

Nines: [0, 9, 18, 27, 36, 45, 54, 63, 72, 81, 90, 99]The given example provides different ways in which the list comprehensions can be used to update the list or generate a new list. Comprehensions provide a short-hand and elegant way of updating sequences. As may be evident, the same code can be written using the conventional for loop and if else conditions.

For instance, in the case of example 1:

# List comprehension:

data = [x+3 for x in data]

# Regular for loop:

for x in range(len(data)):

data[x] = data[x] + 3List comprehension can be a better option once you get the hang of it. It must be noted how the same concept can be extended to include multiple if else conditions as necessary.

List comprehensions are the most commonly used, but there are other types that can also make code pragmatic and simple. The structure and syntax for them are very similar to that of list comprehensions except for the data types that are used.

Dictionary comprehension

The syntax for dictionary comprehension is:

dict = { key:value for key, value in <sequence> if <condition> }

Dictionary comprehension takes one or two lists as input and creates a dictionary out of it. I will now demonstrate how this can be done using only one list and by using two lists.

# Using range() function and no input list

usingrange = {x:x*2 for x in range(12)}

print("Using range(): ",usingrange)

# Lists

months = ["Jan", "Feb", "Mar", "Apr", "May", "June", "July", "Aug", "Sept", "Oct", "Nov", "Dec"]

number = [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]

# Using one input list

numdict = {x:x**2 for x in number}

print("Using one input list to create dict: ", numdict)

# Using two input lists

months_dict = {key:value for (key, value) in zip(number, months)}

print("Using two lists: ", months_dict)The output is:

Using range(): {0: 0, 1: 2, 2: 4, 3: 6, 4: 8, 5: 10, 6: 12, 7: 14, 8: 16, 9: 18, 10: 20, 11: 22}

Using one input list to create dict: {1: 1, 2: 4, 3: 9, 4: 16, 5: 25, 6: 36, 7: 49, 8: 64, 9: 81, 10: 100, 11: 121, 12: 144}

Using two lists: {1: 'Jan', 2: 'Feb', 3: 'Mar', 4: 'Apr', 5: 'May', 6: 'June', 7: 'July', 8: 'Aug', 9: 'Sept', 10: 'Oct', 11: 'Nov', 12: 'Dec'}Note how in case of using two lists, the format it follows is:

new_dict ={key:value for (key, value) in zip(list1, list2)}

Here I used the zip function that combines the two lists. When the two lists are of unequal length, the length of the shorter list is the length of the dictionary.

Set comprehension

The set comprehension deals with the set data type and it’s very similar to list comprehension. The only key difference is the use of curly brackets for sets instead of square brackets as in lists. For example:

set_a = {x for x in range(10,20) if x not in [12,14,16]}

print(set_a)The output is:

{10, 11, 13, 15, 17, 18, 19}You can see the code format is similar to what I used in list comprehensions. For the sake of showing versatility, I used the “not in” keywords to check the values in the list. The output is the values in ranges 10 and 20 that are not present in that list.

Generator comprehension

Generator comprehensions are also very similar to lists with the variation of using curved brackets instead of square brackets. They are also more memory efficient as compared to list comprehensions. For example:

data = [2,3,5,7,11,13,17,19,23,29,31]

gen_obj = (x for x in data)

print(gen_obj)

print(type(gen_obj))

for items in gen_obj:

print(items, end = " ")The output is:

<generator object <genexpr> at 0x102a87d60>

<class 'generator'>

2 3 5 7 11 13 17 19 23 29 31 In the code above, I created a generator object of the class generator instead of a list. The elements in this iterator object cannot be directly accessed and need the help of a for loop and as such, I iterate over these elements and print them.

We will shortly be looking at the difference between map() function and list comprehensions. Assuming we know there is some function called square() that exists as below:

def square(num):

return num * 2Here is the difference between map() function and list comprehensions:

newdata = map(square, data)

newdata = [x + 3 for x in data]

Notice how both map() functions and list comprehension effectively do the same job of modifying iterator sequences such as the list in the example above.

List comprehensions have been a relatively recent development but it does not necessarily mean they are more efficient. Comprehensions have gained popularity primarily for providing cleaner code readability and ease of use. They also provide some added advantages such as providing filtering using if else conditions.

List comprehensions also provide direct return of a list as compared to map() function that returns a map object. It is mainly the clarity that has made list comprehensions popular, but map() functions are still arguably a better choice when it comes to the use of larger sequences.

Additional resources

The following resources will be helpful as additional references in dealing with different concepts related to the topics you have covered in this module.

FunctionMapFilterParadigmPython

Previous one → 5.Procedural programming | Next one → 7.Object Oriented Programming