Debugging Django applications

Debugging

Debugging is the process of identifying and isolating an error, finding the source, and deploying measures to solve the problem.

While making mistakes is a part of programming, correcting errors inside a web framework, such as Django can be particularly difficult.

Unlike errors occurring in a standalone file that can be easily spotted, web projects consists of several interlinked files and dependencies that can make troubleshooting challenging.

While debugging takes patience, it also helps build a better understanding of the internal working of an application.

Mistakes can happen in many forms and at any stage of the development process. These can include :

- missing adding a view

- creating incorrect templates

- missing import statements

- inaccessible resources such as model data

- or even missing a comma in some attributes passed inside a function

As a beginner, seeing the errors and having to troubleshoot can be intimidating. While observation and hands-on practice with web applications are the best means to overcome errors in Django projects, there are tools available that can speed up the process of getting a project up and running.

You already know how to raise a few errors using provided internal implementations. But there are unforeseen errors that occur that also needs to be attended to.

Django has a distinct debugger that appears in the form of a yellow page arrow. You may recall seeing the debug equals true flag on the homepage of the local host after running the server. The Django debugger is enabled by default, and settings for it an be found and modified inside the settings.py file of your project.

While it is a useful component of development, the developers of Django recommend that it should never be used in the production environment. This is because it may expose internal file parts, as well as database and project configuration details to the end user using your website.

This can be prevented by changing the setting to debug equals false.

Other than the default debugger provided by Django, Django, as you know is written in Python and can easily integrate third party libraries that help in debugging.

Let’s now examine a few ways in which you can debug Django applications. This example uses the creating forms project demonstrated earlier.

Immediately, you’ll notice there is a 404 page not found error and this is because you haven’t configured the URL for the local host. Also, notice that this displays in the console in the logger.

NOTE

It’s important to know that the default Django implementation enlists all the steps that Django has performed after you run the command.

Let’s now go to the correct URL. Notice that the logs update at the bottom inside the console.

Now, open the forms.py file. Python specific errors will most likely occur in the console log. For example, if you comment out the shifts constant and save the file, notice an error log displays inside the console. The name error displays with the text, name shift is not defined. If you try to refresh the local host URL in the browser, notice that the page will not load.

However, some other errors are not that obvious. For example, remove the import you passed inside the log form and save the file. Notice that you do not get any error in the log. However, if you refresh the web page, notice that the template for the form disappears except for the submit button that was rendered using static HTML markup.

To prevent this from happening, always ensure you have the right imports and that you pass the correct arguments inside functions.

Let’s say you open the file, my template home.html. Inside the file, remove the code for the CSRF token and save the file. If you go to the local host URL and reload the page, notice that the forms render correctly. Fill out the form and press the submit button. Notice that an error displays stating, forbidden CSRF verification failed. This error specifies that the CSRF token is missing, which is helpful for troubleshooting.

TIP

You can broadly say the yellow page errors are more specific to problems inside Django than Python code.

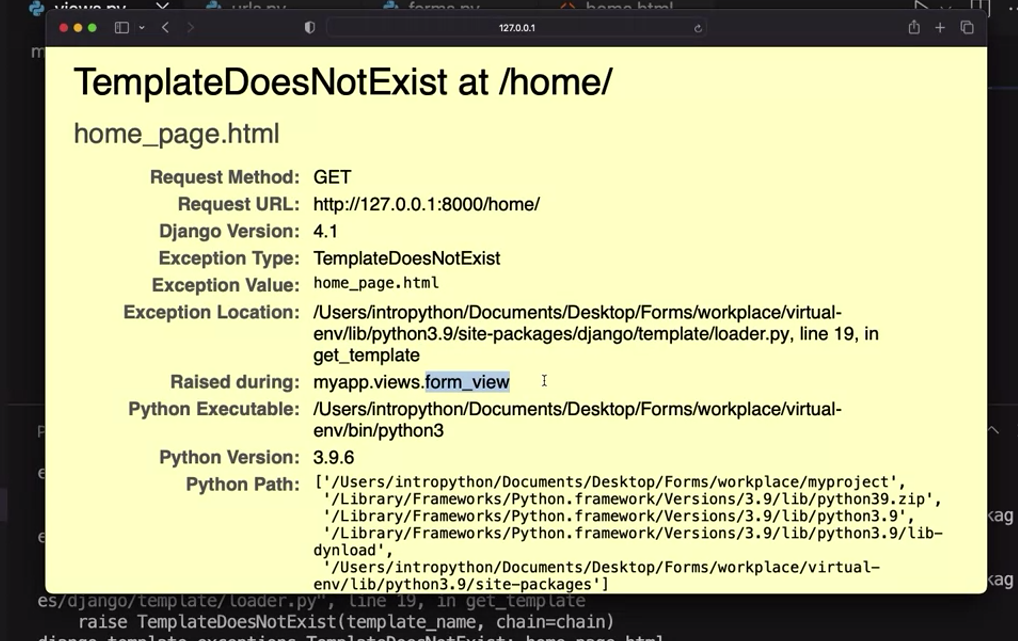

Now, let’s say you go to the files.py file again and misconfigure the template you are trying to render. Let’s say you call this home_page.html and save it again. Once you go to a template page, you get an error such as template does not exist in the particular path.

First, it specifies the exception location, and you can get a hint from get template and how it is raised during form view.

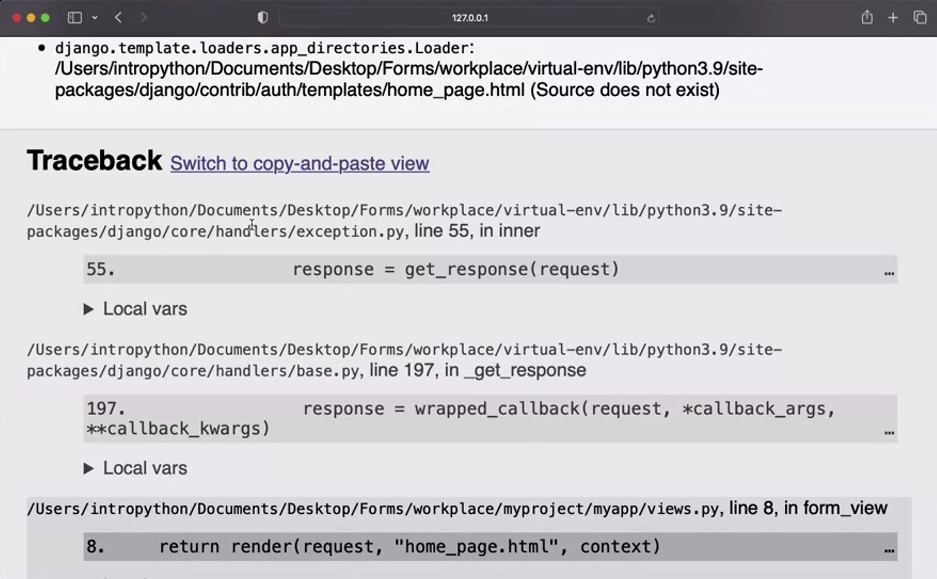

Next, if you keep scrolling, you get a stack, which is called the trace back stack. It contains Python code in sequential order with a particular line highlighted, which will likely be the place of the error.

You can also convert this to switch to copy and paste view. When you change this, you get a much cleaner interface, mentioning all the details.

You can additionally click on, share this trace back on a public website, which when clicked, will take you to debase.com. This page displays convenient clipboard content that you can share on different forums.

If you scroll down further, there’s information about the dictionary containing all available HTTP header information called meta.

On further scrolling, you can find details inside the settings and all of these are potentially helpful.

TIP

Regarding debugging, you can never apply a one rule for all approach. With practice, the number of errors you encounter will slowly decrease. A systematic and patient approach in dealing with these projects is the best way forward.

Testing in Django

Testing is an important component in the software development lifecycle. While debugging is more driven towards removing the application’s errors and bugs, testing considers metrics for quality, reliability and performance.

Every language and framework has many testing options and developers make appropriate selections based on the project’s requirements.

Unit test

A popular method is unit testing, which you can use to isolate a function class or method and only test that piece of code.

When working with unit testing, you need the following baseline information:

First, the test targets granular features in your code, the smallest possible testable units. Then the output of the test will be pass fail or an error.

In Django. The unit test module uses a class based approach. You add the tests inside a class that inherits a class called test case from the Django test package.

from django.test import TestCaseSuppose you wrote a model called reservation and want to test it. First import that TestCase class that inherits test case, then import the reservation model.

from django.test import TestCase

from myapp.models import Reservation

class ReservationTestCase(TestCase):

def createReservation(self):

Reservation.objects.create(name="John", seat_count=4, time_entry=10:10)

def test_seat_count(self):

"""The seat count is ensured to be less than 8"""

customer = Reservation.objects.get(name="John")

# insert Assertion to test conditionOnce you create the tests, use the command :

python3 manage.py testAdditionally, you can add specific configurations to run all tests within a specific package. For example, run the command:

python3 manage.py test reservationsTo run a specific test case, use the command:

python3 manage.py test reservations.tests.ReservationTestCaseOur suppose you want to run a specific test method inside a test case, for example, a method to calculate the seat count. You can run the command like:

python3 manage.py test reservations.tests.ReservationTestCase.test_seat_countTIP

It’s important to know that developers generally add these test cases under one or more files created under specific app folders. In a small project it’s common for developers to name the file

tests.py. In large projects that may contain multiple test files, it’s common for developers to use names liketest_models.pyandtest_views.py.

Example

# models.py

from django.db import models

class Reservation(models.Model):

first_name = models.CharField(max_length=100)

last_name - models.CharField(max_length=100)

booking_time = models.DateTimeField(auto_now=True)

def __str__(self):

return self.first_nameThe ==auto_now== field inside the booking time logs the system’s current time and is set to true.

# tests.py

from django.test import TestCase

from datetime import datetime

from .models import Reservation

class ReservationModelTest(TestCase):

def setUpTestData(cls):

cls.reservation = Reservation.objects.create(

first_name = "John"

last_name = "McDonald"

)

def test_fields(self):

self.assertIsInstance(self.reservation.first_name, str)

self.assertIsInstance(self.reservation.last_name, str)

def test_timestamps(self):

self.assertIsInstance(self.reservation.booking_time, datetime)setUpTestData is a method present inside the test case that you use to add data inside the model. So in this example data is entered for the first name and the last name. It is important to know that booking time automatically updates as the auto_now parameter is set to true.

You perform the check using the assert statements to check both the first name and last name are of the string data type.

python manage.py makemigrations

python manage.py migrateWARNING

The final part of this step is to remember to add the

classmethoddecorator; Since this is a class method.

# tests.py

from django.test import TestCase

from datetime import datetime

from .models import Reservation

class ReservationModelTest(TestCase):

@classmethod

def setUpTestData(cls):

cls.reservation = Reservation.objects.create(

first_name = "John"

last_name = "McDonald"

)

def test_fields(self):

self.assertIsInstance(self.reservation.first_name, str)

self.assertIsInstance(self.reservation.last_name, str)

def test_timestamps(self):

self.assertIsInstance(self.reservation.booking_time, datetime)python manage.py testSub-classing Generic Views

In this reading, you’ll learn about the class_based generic views.

You can implement the view layer with function or class-based views in a Django application. You declare a class by extending the django.views.View class and define get() and post() methods inside it to handle the HTTP requests. The URL pattern connects the path to the class with the as_view() method of the View class.

A quick example of class view:

from django.views import View

class NewView(View):

def get(self, request):

# View logic will place here

return HttpResponse('response') The URL pattern in urls.py is updated as below:

#urls.py

from myapp.views import NewView

urlpatterns = [

path('about/', NewView.as_view()),

] Django provides class-based generic views to make the development process much easier and faster. In this reading, you’ll discover how the generic views are implemented.

The most frequently used generic views are:

- TemplateView

- CreateView

- ListView

- DetailView

- UpdateView

- DeleteView

- LoginView

Difference between Function View and generic view

Let’s take a simple example of rendering a Hello world template. You should render the template as the HTTP response – the return value of the function. The view function for this purpose would be as follows:

from django.shortcuts import render

from django.http import HttpResponse

def index(request):

template = loader.get_template('myapp/index.html')

context={}

return HttpResponse(template.render(context, request)) As you may have already learned, the app package folder exists inside the project’s outer container folder. The myapp app is created in the Django project named myproject.

In the myapp/urls.py, define the URL pattern:

path('/', views.index, name='index') You can include the URL definitions of myapp in the project’s URL configuration:

urlpatterns = [

. . . ,

path('myapp/', include('myapp.urls'))

] Use a TemplateView class instead. Simply define a class extending it and set the template_name attribute.

from django.views.generic.base import TemplateView

class IndexView(TemplateView):

template_name = 'index.html' The corresponding URL pattern should incorporate this:

path('/', IndexView.as_view(), name='index') Advantage of function-based views

- Simple to implement.

- Easy to read.

- Explicit code flow.

- Straightforward usage of decorators.

- good for one-off or specialized functionality.

Disadvantages of function-based views

- Hard to extend and reuse the code.

- Handling of HTTP methods via conditional branching.

Advantages of Class-based views

- Code reusability.

- DRY — Using CBVs help to reduce code duplication.

- Code can be extended to include more functionalities.

- class with different methods for each http request instead of conditional branching statements inside a single function-based view.

- Built-in generic class-based views.

Disadvantages of Class-based views

- Harder to read.

- Implicit code flow.

- Use of view decorators require extra import or method override.

Requirements of a generic view

- If the view needs a model to be processed, it should be set as the value of model property of the view.

- Each type of view looks for a template name with

modelnamesuffixed by the type of generic view. For example, for a list view processing employee model, Django tries to findemployee_list.html. - The generic view is mapped with the URL with

as_view()method of the View class.

Let’s now build a subclass for each of the respective generic view classes to perform CRUD operations on the Employee model:

class Employee(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=100)

email = models.EmailField()

contact = models.CharField(max_length=15)

class Meta:

db_table = "Employee" CreateView

The CreateView class automates the creation of a new instance of the model. To provide a create view, use the sub-class of CreateView:

from django.views.generic.edit import CreateView

class EmployeeCreate(CreateView):

model = Employee

fields = '__all__'

success_url = "/employees/success/" A model form based on the model structure is created by this view and passed to the employeeCreate.html template:

<form method="post">

{% csrf_token %}

<table>

{{ form.as_table }}

</table>

<input type="submit" value="Save">

</form> The URL path is updated by mapping the "create/" path to the as_view() method of this class:

from .views import EmployeeCreate

urlpatterns = [

. . .

path('create/', EmployeeCreate.as_view(), name = 'EmployeeCreate') ,

] When the client visits this URL, they are presented with the form. The user fills and submits the employee details, which are saved in the Employee table.

ListView

Django’s django.views.generic.list module contains the definition of ListView class. Write its sub-class to render the list of model objects.

The EmployeeList class is similar to the CreateView sub-class except its base class.

from django.views.generic.list import ListView

class EmployeeList(ListView):

model = Employee

success_url = "/employees/success/" The template required for this view must be named employee_list.html. Django sends the model object in its context. Using the DTL loop syntax, you can display the list of employees:

<ul>

{% for object in object_list %}

<li>Name: {{ object.name }}</li>

<li>Email: {{ object.email }}</li>

<li>contact: {{ object.contact }}</li>

<br/>

{% endfor %}

</ul> If the user visits http://localhost:/8000/employees/list, the browser lists all the rows in the employee table.

DetailView

The generic DetailView is found in the django.views.generic.detail module. Now, create its sub-class, EmployeeDetail (much the same way as EmployeeList). Note that this view shows the details of an object whose primary key is passed as an argument in the URL. So, add the following path in the app’s URL pattern:

path('show/<int:pk>', EmployeeDetail.as_view(), name = 'EmployeeDetail') Again, the View object fetches the model instance and passes it as a context to the employee_detail.html template, which displays its attributes with template syntax as follows:

<h1>Name : {{object.name}}</h1>

<p>Email : {{ object.email }}</p>

<p>Contact : {{ object.contact }}</p> Assuming the URL visited is /employees/1, the Employee record with primary key=1 will be displayed.

UpdateView

This is another generic view, defined in django.views.generic.edit module. It renders a form in which the new values of the model attributes can be submitted. Set the fields attribute to '__all__' or to a list of updatable fields.

from django.views.generic.edit import UpdateView

class EmployeeUpdate(UpdateView):

model = Employee

fields = '__all__'

success_url = "/employees/success/" Since this view is intended to update the data of a given model instance, its URL path must be configured accordingly:

path('update/<int:pk>', EmployeeUpdate.as_view(), name = 'EmployeeUpdate')The example URL that invokes this view is /employees/1.

The UpdateView class renders the template with its name having update_form as suffix:

#employee_update_form.html

<form method="post">

{% csrf_token %}

<table>

{{ form.as_table }}

</table>

<input type="submit" value="Save">

</form> DeleteView

Lastly, the generic view performs the delete operation on a model’s given instance. It is present when editing the sub-module of django.views.generic module:

from django.views.generic.edit import DeleteView

class EmployeeDelete(DeleteView):

model = Employee

success_url = "/employees/success/" You need to pass the primary key of the Employee model to this. So, the URL path is set as:

path('<delete/int:pk>', EmployeeDelete.as_view(), name = 'EmployeeDelete') The employee_confirm_delete.html template asks for confirmation from the user before removing the model instance.

<form method="post">

{% csrf_token %}

<p>Are you sure you want to delete "{{ object }}"?</p>

<input type="submit" value="Confirm">

</form> In this reading, you got to know about the class-based generic views to perform CRUD operations. Generic views are much easier to write than the function_based view, although both have their own advantages and disadvantages.

Additional resources

Here is a list of resources that may be helpful as you continue your learning journey.

Testing overview – Django official

Django Advanced Testing topics

Add unit testing to your Django project

Adding Django apps – Extended information

PythonDjangoDatabaseTestDebugCRUD

Previous one → 13.Working with Templates | Next one → 1.Introduction to APIs